Sorry for the strong language in the title, but it’s true: the rock salt you go to sprinkle over the icy sidewalk every year is actually a pretty mediocre substance. Sure, it melts ice, but it’s not as efficient as other substances. You’d be better off saving that salt for your next soup or gumbo, or whatever it is you’d like to cook. Why is salt not that great at melting ice? We’ll delve into the very simple structure of salt to find out the answer, and then we’ll see what you should be using instead to get a much better, less slippery sidewalk!

Sorry for the strong language in the title, but it’s true: the rock salt you go to sprinkle over the icy sidewalk every year is actually a pretty mediocre substance. Sure, it melts ice, but it’s not as efficient as other substances. You’d be better off saving that salt for your next soup or gumbo, or whatever it is you’d like to cook. Why is salt not that great at melting ice? We’ll delve into the very simple structure of salt to find out the answer, and then we’ll see what you should be using instead to get a much better, less slippery sidewalk!

You might already know the chemical formula for table salt is NaCl. It just means for every sodium atom, there is a chloride atom to go with it. It’s a very simple substance, but it’s not a molecule — a term which is reserved for discrete groups of atoms (sugar molecules or water molecules, for example, are always the same and don’t associate with each other so much that we can’t separate them). Salt is really an ionic substance, which just means that instead of having a discrete, separate “NaCl” molecule, it builds on itself, and each sodium bonds to a couple of chlorides, and each chloride finds a couple of sodiums. The end result is a crystal, just like diamond, that’s highly ordered because all the atoms bond in the exact same way with all the others. This is why coarse salt comes in those very geometrically ordered crystals — it’s the natural way that salt comes, all sharp lines and angles.

You might already know the chemical formula for table salt is NaCl. It just means for every sodium atom, there is a chloride atom to go with it. It’s a very simple substance, but it’s not a molecule — a term which is reserved for discrete groups of atoms (sugar molecules or water molecules, for example, are always the same and don’t associate with each other so much that we can’t separate them). Salt is really an ionic substance, which just means that instead of having a discrete, separate “NaCl” molecule, it builds on itself, and each sodium bonds to a couple of chlorides, and each chloride finds a couple of sodiums. The end result is a crystal, just like diamond, that’s highly ordered because all the atoms bond in the exact same way with all the others. This is why coarse salt comes in those very geometrically ordered crystals — it’s the natural way that salt comes, all sharp lines and angles.

Pretty much any ionic compound like salt will dissolve in water because of this strange bonding behavior. Water grabs each atom and pulls them apart from each other, and when all the sodiums and chlorides have stopped associating with each other, it’s dissolved and invisible!! In other words, table salt in water separates into its constituent atoms (in this case, called ions). As with all of science, it’s more complicated than that, but we’ll save that for another time.

The other key thing you might not know is that ice is not slippery. Yes, ice is not slippery, but water is. Ice on the sidewalk has a very thin layer of water on top of it, which makes it hard to walk on. Any amount of pressure or heat creates this layer, so there’s literally no way for you to walk only on ice — you’re always walking on the buffer of water above it. Now imagine dissolving some table salt into that top layer of water. Just like in a glass of water, the atoms of salt will come apart and associate with water instead. Since it’s probably below freezing at this point, the water would really, truly like to become frozen water, which some people call ice. Thanks to salt, it no longer can.

The other key thing you might not know is that ice is not slippery. Yes, ice is not slippery, but water is. Ice on the sidewalk has a very thin layer of water on top of it, which makes it hard to walk on. Any amount of pressure or heat creates this layer, so there’s literally no way for you to walk only on ice — you’re always walking on the buffer of water above it. Now imagine dissolving some table salt into that top layer of water. Just like in a glass of water, the atoms of salt will come apart and associate with water instead. Since it’s probably below freezing at this point, the water would really, truly like to become frozen water, which some people call ice. Thanks to salt, it no longer can.

The reasoning is pretty simple — imagine a little spherical sodium ion (just an atom, remember now) settling into some liquid water, swishing around with all the other moving cells. When things become solid their movement is largely restricted, and water in particular tends to freeze into its own crystal structure. Take a look at the picture to the right to see how water molecules arrange themselves when they become ice — there’s plenty of free space for ions to get in the way and prevent this structure from coming together. Imagine a big ol’ sodium or chloride atom just forcing its way into those nice little bonds there — it’d be a little harder for the ice to form. Because of the way water freezes, it’s less dense as ice than it is as liquid water, so ions have an easier time jumping into the fray and ruining ice’s day.

The only way water is going to freeze now is if it loses even more heat — it has to lose a little bit more heat, which means molecules will move around a little less, and at some point their energy is sufficiently low to allow them to bond to each other, albeit imperfectly. Ice will do this to account for the disruption in bonding from the salt. At 32 degrees, water wouldn’t freeze with salt in it. So Mother Nature drops the temperature a few more degrees, and water is able to freeze again. Yay!

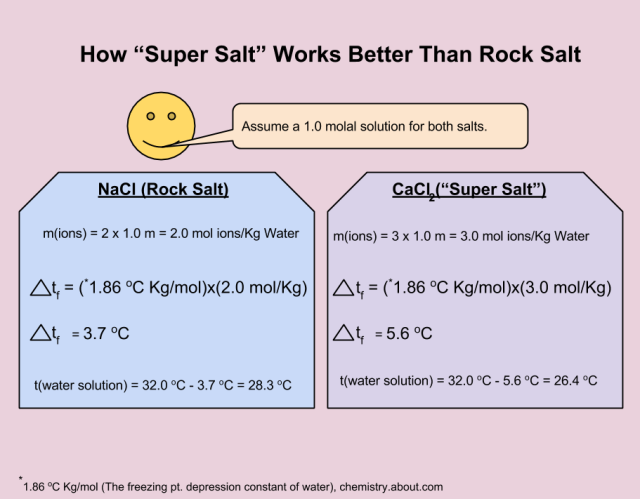

Each mole of CaCl2 is more densely packed with ions, making it the better choice for melting ice.

So why is rock salt weaksauce for melting ice? It’s only made of two ions – sodium and chloride ions. An equivalent amount (chemists use moles to compare “amounts” of things) of CaCl2, called calcium chloride, breaks apart into three ions — it’s 50% better at disrupting the bonds needed to make ice. In fact, any ionic compound with more than just two atoms per formula unit. A formula unit is just the smallest discrete “molecule” of a substance, except that ions make giant crystals instead of staying as separate molecules, like water or sugar. Imagine if 100 water atoms could all associate to form a single giant water crystal — the formula unit would be H2O because that’s the formula unit that makes up the crystal as a whole.

There are many more ionic compounds that are more effective than rock salt, including ammonium sulfate and magnesium chloride. In other words, when we buy rock salt because it’s the cheapest de-icer, we’re shortchanging ourselves. We could be using a lot less “stuff” on our sidewalks while getting the same effect, or using the same amount compared to rock salt and get an even more effective result.

Winter’s grasp has finally let go of us, but keep these concepts in mind for next year – if you have to make a choice between rock salt and calcium chloride at the Get-rid-of-ice store, give it a little more thought. You just might stretch your hard-earned dollars a little farther.