Digestion is a huge topic, as we learned in the last discussion. This time, let’s zoom in on a quick little fascinating molecule that controls a lot about the way our food is digested. We’ll start by looking at an enzyme called salivary amylase, and see if we can apply it to some larger principles about humans around the world.

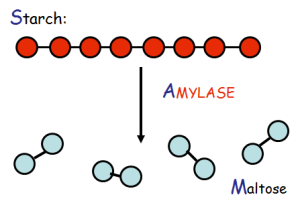

Amylase in a nutshell, retrieved from http://muirbiology.wordpress.com/national-45/unit-1-cell-biology/6-proteins-and-enzymes/

Salivary amylase is an enzyme, meaning that it’s a small proteins whose function is to make it easier for reactions in the body to take place. To give you a better idea of what it does, it’s present in your saliva when you’re eating, so that whatever you’re putting into your mouth begins to break down right away so you can absorb it more easily. Without salivary amylase, your food wouldn’t be broken down as easily, and you’d have to work harder to digest and metabolize. The word “amylase” in the enzyme’s name refers specifically to the breakdown of starches — potatoes, pasta, pizza, toast — meaning that this particular enzyme only breaks down carbohydrates, and it does so the second food enters your mouth

Yeast feed on glucose, and the result is alcohol – the kind we drink in beer and liquor!

If you know any home beer-brewers, then you might be interested to hear that this is a common treatment for the yeast in the beer. The yeast normally feed on glucose, the smallest unit of sugar. If we add long chains of starches, we can also add amylase to cut up those chains into maltose (similar to glucose) molecules that the yeast can eat. If you want to make a loaf of bread from scratch, the flour you add will serve better as yeast food by first breaking it down by amylase.

So now we know what this enzyme does: it breaks down carbohydrates into simple sugars at the first level of digestion — eating! What’s really interesting here, though, is that across the planet, different populations of humans (and other animals!) have evolved to use this enzyme better than others. For example, a human’s DNA contains way more copies of this enzyme. In other words, any time a cell makes proteins, it makes more copies of this amylase enzyme. Think of it as writing on a computer: if you type the letter “a” one time, you’ll only get one letter on the screen. Hold down the key, though, and you’ll generate 15 or 20 copies of the letter. Our DNA does the same thing, with the end result being that for the same stretch of genes, our bodies produce more copies of the enzyme, instead of just one or a few.

Humans are complex eaters: we’ve been eating starches, fat, and proteins forever and ever, and our bodies have had to come up with different ways to digest all of these components. In a 2010 issue of American Scientist, the following is written:

The salivary amylase levels found in the human lineage are six to eight times higher in humans than in chimpanzees, which are mostly fruit eaters and ingest little starch relative to humans.

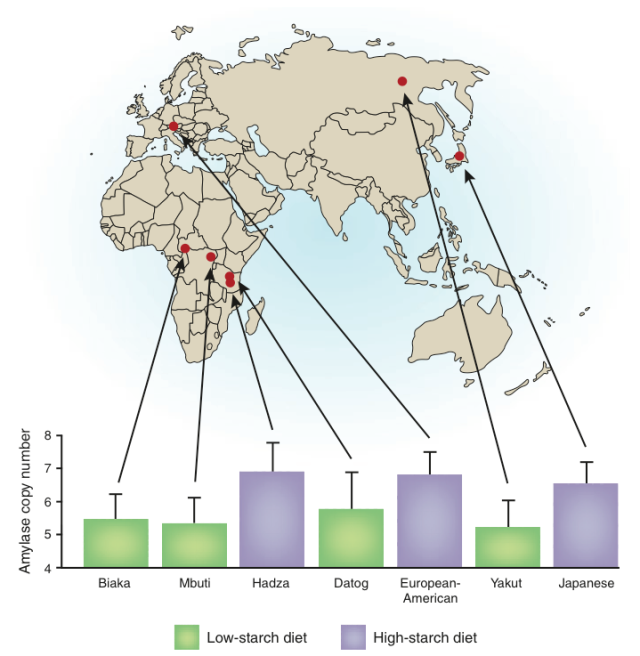

So chimpanzees don’t eat a lot of starch. Therefore, they don’t need a lot of amylase to digest food. Now let’s take a look at the other end of the spectrum. If you’re from the USA or Canada, you probably don’t eat rice all that much. Of course, you probably know that in Asian countries like Korea, China, and Japan, rice is eaten at nearly every meal and is the staple food of those cultures. Who would you think would have a higher level (more copies) of salivary amylase, someone from the US or someone from Japan? Before you answer, look at the nutrition chart to the right: white rice is primarily carbohydrate, which as we know, is converted to simple sugars through digestion (and salivary amylase when it hits your tongue!!)

Hopefully you’re having the following train of thought right now: Asian populations eat rice more frequently, so if they have more copies of salivary amylase, they’re better suited to eating and digesting rice on a regular basis. Indeed, this is the case.

For example, a Japanese individual had 14 copies of the amylase gene (one allele with 10 copies, and a second allele with four copies)… In contrast, a Biaka individual carried six copies (three copies on each allele). The Biaka are rainforest hunter-gatherers who have traditionally consumed a low-starch diet.

Perry, GH, et al. Diet and evolution of human amylase gene copy number variation, Nature Genetics 39:1256-1260 (2007).

The bolding is for emphasis and done by me to show you the huge difference between cultures. A Japanese individual has waaaay more copies of this gene, and thus way more copies of the protein, in their saliva and bodies. The more copies, the easier it is to eat rice and put it to metabolic use. See the chart below for more details:

This chart was obtained from another awesome science blog, available here: Confusedious

This brings us to another idea: if you are or have friends of Asian descent, it’s quite likely that even if you live in the USA, your genes carry more copies of the amylase gene and you have an easier time digesting rice and other starches. Someone with genes from a low-starch culture would carry less, and would be able to tolerate fewer starches before his or her body began to show signs of metabolic dysfunction (however slight and mild they may be).

So we’ve seen here that a single gene for starch breakdown has a huge impact on how we digest food, and that the gene itself is abundant in places where it’s been historically advantageous. In regions where it’s not so important, modern populations will carry fewer copies of the gene because their ancestors ate less starch. It just goes to show you that even though we’re all living in a connected world, our genes are still responsible for our individual responses to the food we eat. No two individuals are the same when it comes to food metabolism because we’re all an amalgam of our forebears tracing back a lineage of hundreds of thousands of years.